2007 Rainer Beßling

Rainer Beßling // Measurement – Norm – Format | Colour

Rainer Beßling // Measurement – Norm – Format | Colour

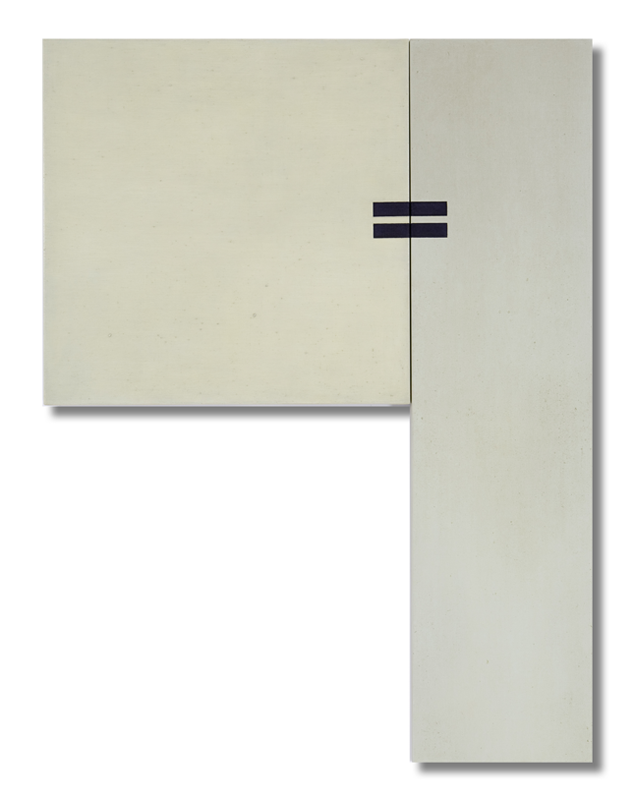

equal 7 – 2m² 2006 200x150cm, 2-parts oil/canvas

Monochrome surface areas of different colour shades of colour contrasts crash into each other. Surfaces of similar size appear in different formats. Demarcation marks indicate a picture space forming a cut-out. A window and a field emerge where picture standard and individual interpretation, world and world view, memories and representation of perceptions meet. Sometimes parallel colour bars or equal signs function as hinges linking areas of different colours and formats. At other times lines function as separators to demarcate an open inner space. Pictures also appear in fragments and the viewer immediately feels invited to act as co-author, complementing active perception with his or her own history.

Sabine Straßburger has consistently refined her pictorial language. In her latest works she pursues her basic themes in condensed form. In earlier works the artist used archaic signs placed onto a blottesque grounding. Undecipherable though they are the signs still claim a meaning, creating an aura of mystery and turning the spectator into a tracker and picture archaeologist. Onomatopoeic titles heighten the impression of discoveries from distant cultures and past times.

In the works that follow, languages particles replace the indistinct signs: By taking this step, Straßburger’s artistic practice has, at an early stage, gained a double perspective in her aesthetic perception. According to her understanding of art, language and painting belong together. Her construction of pictures resembles that of language, because she does not separate pictures from their linguistic disclosure. But she also uses and accentuates the openness which distinguishes pictures from texts.

Thus, for instance, in her picture series she makes use of the linguistic signs between words: full stops, colons and brackets insert themselves into the finely resonating colour material. Punctuation represents the linguistic corset, structuring and ordering the flow of the text, combining what belongs together, building structures, organizing levels into layers and clarifying connections. If used in isolation and thereby elevated from its supporting role to a leading one, punctuation highlights the gaps in language in both senses. The space between a pair of brackets becomes an area for the viewer’s projections. Simultaneously, the sign points to the connotations and correspondences in language and the sound behind words which meets with a different reception from every ear.

There is another constituent characteristic of language to be found in Sabine Straßburger’s pictorial art: convention and generalization. Language locks experiences and an outlook on life into set formulae, links the physical presence of signs to the material world, renders individual views of the world abstract through its communication-promoting formulaic structure and still continues to be suitable as a receptacle for objective as well as subjective contents.

Sabine Straßburger exemplifies the conventions at the origin of pictures, by linking them to a discovery she made when viewing 19th Century French art. She noticed that certain formats correspond to certain genres. The measurements for portrait, landscape and seascape paintings follow fixed norms for an astonishing number of years. One explanation may be the correspondence of the format to the subject. But Straßburger is more interested in the principle governing the standardization than in the reasons for a specific convention.

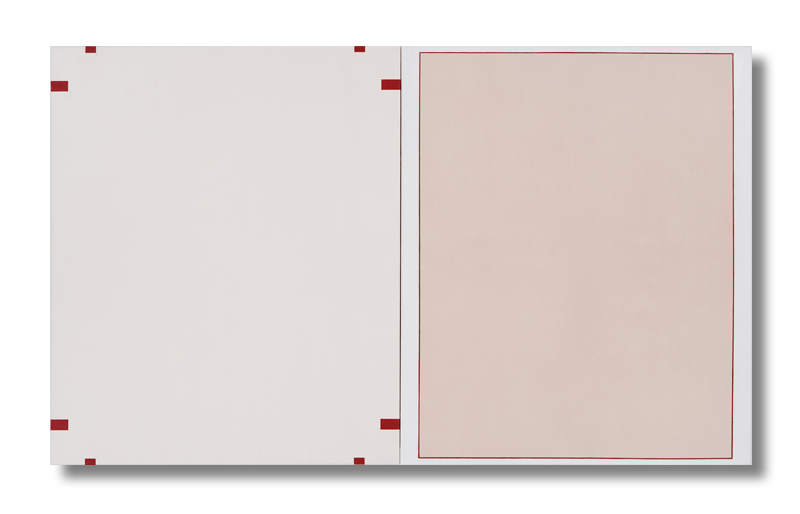

No. 50 [french portrait] 2005 120x200cm, 2-parts oi /canvas

The artist takes the format norms back to their structural basis and shows them freed of motive and figure, determined purely by area. In doing so, she applies various methods of constraint: bars to maintain distances, register marks, lines to form a rectangle. Standardized measurements identified by such measurement scales determine the frame of what happens in the picture. They demarcate the picture space onto which reality is projected and where it is transformed. The inner picture space is related to its surroundings. The picture area as picture content oscillates between openness and constraint.

No. 6 [french portrait] 2003 60x100cm, 2-parts oil/canvas

Sabine Straßburger uses the formats she found into her own frames. Personally, she likes extreme bar-shaped measurements which cannot accommodate perceived reality and imagination without a clearly defined personal opinion. Convention and individuality rub up against each other. In certain cases the artist makes reference to details in historical paintings reduced to their normative structure and lets the voids play along as clear inspiration for the viewer’s inspiration.

While making measurement and norm the subject of her art, other frames of reference than the correspondence between format and genre can be detected, such as the proportionality between artist and picture, between viewer and picture, between picture and space. The artist’s physical presence determines extension and impact of the picture. There is a difference between showing a picture on a monitor in detail or in its entirety; and also to a viewer bodily approaching a picture in a real room and seeing it at various distances.

teils [french portrait no. 60] 2006 175x130cm, 2-parts oil/canvas

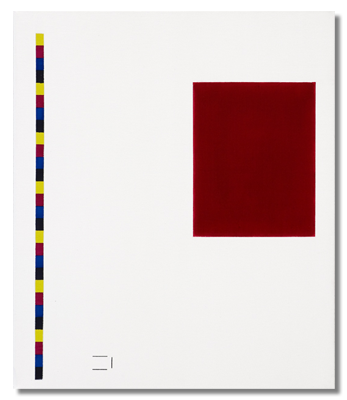

In Straßburger’s paintings her interest in patterns or organization, in norms and measurement is inextricably linked to the organizational process of picture creation itself. Just as in analysis the format itself is treated as content, and presentation and reproduction appear as part of the composition. Colour mixing becomes the subject matter itself through her reference to the four primary printing colours. A pair of „identical“ pictures side by side demonstrates the futility of creating the same painting twice.

No. 2 [french portrait] 2007 60x50cm oil/canvas

The artist reflects what we remember of format and colour and shows how format and colour steer perception. She plays with the seemingly objective pictorial reality which is refracted differently by every viewer. The construction of reality occurs through the combination of impressions and experience. Viewing pictures is also a highly selective and active process. The picture is but the impulse. Every viewer perceives differently, remembers differently. With time, a picture solidifies. This impressions lasts, but does not necessarily correspond to the original. In Straßburger’s works the picture is presented straight away in a manner that requires viewers to compose and continue formulating it.

teils [french portrait no. 40] 2005 120x35cm oil/canvas

We respond positively to this offer to construct a picture ourselves, because of the aura and suggestive power of Sabine Straßburger’s paintings. Thinking of conditions under which a painting affects us is short-circuited with the immediate effect of the picture. It is colour, more than anything else, which stops analytical and symbolical, reflective and representational painting from being contradictory.

Colour adds poetry and emotion to the objective and investigative process. Yet colour also represents ambivalence of perception. Supposedly clearly distinguishable and easy to fit into a system, colour is really the most difficult of all artistic tools to determine. Even people’s basic ability to see colour varies. Colour reception is a complex process: light, surrounding colours, saturations, size and format of the coloured area, the sculptural appearance of the coloured canvas all contribute to the effect. It is nearly impossible to generalize colour. Colour carries within it the artist’s personal experiences and emotional potentials. It conveys expression as well as the intention to cause an effect. Through colour the substance and soul of things acquire a shapeless presence.

In Sabine Straßburger’s paintings the process of colour selection is laid bare. Colour charts explain the composition and layers. By referring to the practical development process the artist suppresses the need to wonder about the state of mind or experience that lead her to choose a certain colour. By making colour objective, the viewer is focused on what happens in the picture, making him more open to its content.

No. 40 [french marine] 2005 100x135cm oil/canvas

The artist’s choice of oil means her paintings develop slowly and show their material composition. Paint application is visible and distinguishable. Straßburger’s unexhibited paintings shed light on her development through trial and error. Her practical search for the correct combinations of inner and outer surrounding colours are locked in the calmly pulsating layers of paint.

The extent to which colour itself functions as symbol and content carrier is evident in a number of family portraits painted by Straßburger following her French „format discoveries“: the colours in the formats identify the protagonists of family life without them having to be portrayed as figures. Colour as an archetypal distinguishing agent retains its original signal strength also in the aesthetic context. Figures and faces are largely genetically determined. To the artist what is behind them is more important. Her portrait formats with their layers of paint and tailored periphery combine into an overall composition that can also be interpreted as a self-portrait. And, we are lead to believe, most viewers tend to look for themselves in any portrait.

Time is enshrined in the application of paint and the format is no static entity either. Instead, it suggests various speed settings with its different directions of movement. In contrast to the linear organization of language, everything is presented simultaneously in a picture. Time is stopped at different levels and frozen. Individual strands and layers can be isolated and pursued in a linear manner. The composition of a picture, however, attains its full impact only in the simultaneous nature of the individual elements. Everything remains intertwined. Beginning and end of a timespan are made to float side-by-side. The difficulty in deciphering a picture is due to the viewer’s habit of linear reading. The eye moves selectively in front of a picture.

No. 15 [french landscape] 2000 60x155cm, 2-parts oil/canvas

The time spent on a picture’s creation; a subjective and objective, historical and individual time; meets with the time spent in perceiving it. Viewing cannot be sped up without missing something. The world, life, things, pictures all need time. It is also a question of values. New pictures can only connect with the optical memory, enter into memory, and gain and promote and identity, if perception is given time. Pictures that call on us for a personal, proportionate commitment based on personal perspective and at one’s own speed, emancipate the viewer from the seductive power of the visual.

In Straßburger’s paintings a pivotal narrative component is combined with the aspect of time. Her paintings, which occasionally confess their connection with language, contain stories and history and deal with questions of practical philosophy through overstatement of the structure and consolidation of the content. Organizing a view on reality, structuring work and thinking are not only the object of aesthetic practice; aesthetic practice as the production and reception of art can be seen as an excellent training arena for a self-determined life.

1:1 [french landscape no. 50] 2007 160x370cm, 2-parts oil/canvas

1:1 [french landscape no. 50] 2007 160x370cm, 2-parts oil / canvas

Finding a format means finding appropriate principles for one’s life; achieving clarity on the picture surface stands for sorting one’s thoughts and feelings. Formulating more precisely is essential when time can no longer be thought of as endless. A decision has to be made: To forget or to go on the offensive with what one has experienced. By generalizing the past, it can be used as a yardstick for the future. By tidying up and airing, the world is made easier to understand and life becomes more worth living.

In this way the artist sharpens perception by directing our regard at the basics and the essential – not only in pictures. Painting means coming back to and leaving traces. It is thinking backwards, but also forwards. Sabine Straßburger offers an alternative to the insidious loss of perceptive and picture deciphering culture: A school of seeing – a course in ethical thinking. She quotes Einstein: „Everything should be as simple as possible, but not simpler.“ That sentence could serve as the guiding principle of her aesthetic practice.

Translated by Joan Leisewitz